Mum’s The Word

Reflections on motherhood

From 9 March 2024 Eileen Cooper’s work will feature in the Hayward Gallery Touring exhibition Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood.

In response to the exhibition, and of a theme that has been central to Eileen Cooper’s work for decades, a cohort of art world mothers and friends of Eileen were invited to take part in this online exhibition. Each of them was asked to comment on their lived experience of motherhood. With few rules or guidelines these mothers have kindly provided thoughtful, provocative, and at times painful, versions of their own very personal views on this uniquely female experience. Eileen and I thank them for their trust, their bravery, their creativity and honesty.

Kathleen Soriano, Curator

March 2024

Contributors:

Hettie Judah Curator, Author and Art Critic

Eliza Gluckman Director, Government Art Collection

Soheila Sokhanvari Artist

Clare Woods RA Artist

Hannah Perry Artist

Caro Howell Director, Imperial War Museum

Rejina Pyo Fashion Designer and Creative Director

Denise Riley Poet

Helena Lee Author and Features Director of Harper’s Bazaar, Editor of Bazaar Art

Eileen Cooper RA

Hettie Judah

Curator, Author and Art Critic

Putting Down Roots

1985

—

Oil on canvas

243.3 x 182.2cm

Collection Arts Council of Great Britain

For me, Eileen Cooper’s Putting Down Roots recalls the fragmentation of the self experienced by many mothers – the feeling of still being the same person but also of having changed entirely.

It is common to describe a new mother as having lost her sense of self, as though the new identity erases the previous one. Putting Down Roots instead suggests multiple selves co-existing, each contributing to something rich and complex – look at all those roots and branches and bodies entwining!

Cooper sees the darkness and competing pressures in all of this - the feet of one body are firmly planted on the torso of the other, pinning it to the ground – but the overwhelming feeling here is of joy and wonder.

Eliza Gluckman

Director, Government Art Collection

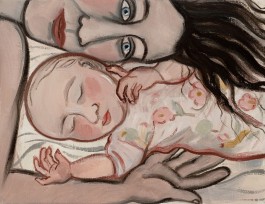

Sleep

2021

—

Oil on canvas

23 x 30cm

Private collection

Motherhood suggests a stage of life, but once unlocked is of course a lifelong state that shifts over time. As a term it still makes me think of the baby stage – the irony of Eileen’s Sleep – an impossible elusive goal in the early years.

A time when time dissolves around you – day and night merge – anything seems possible and yet getting through the day is a miracle. I had a wonderful boss in the years preceding motherhood who explained – ‘You don't really sleep for eight years’ – a joke perhaps, but I came to know what she meant.

What is confusing now, as I live through the mind-blowing changes of teenagers, is how motherhood fits with the push and pull of love and rejection.

Personal turbulence of what signals to give, when to let go, when to reach out and catch them. I am now at the stage of Eileen's Voyage, one child looking over the edge of the boat, getting ready to launch. As a swimmer this speaks – having to stand back and see if I've taught him enough to not only keep his head above the water, but also to be enveloped and enjoy it.

Soheila Sokhanvari

Artist

Mother’s Day

2021

—

Oil on canvas

106 x 81cm

Collection Artist

Mother, A Cradle to Hold Me by Maya Angelou

It is true

I was created in you.

It is also true

That you were created for me.

I owned your voice.

It was shaped and tuned to soothe me.

Your arms were molded

Into a cradle to hold me, to rock me.

The scent of your body was the air

Perfumed for me to breathe.

Mother,

During those early, dearest days

I did not dream that you had

A large life which included me,

For I had a life

Which was only you.

Clare Woods RA

Artist

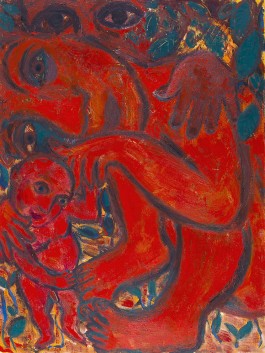

The New Baby

1985

—

Oil on board

60 x 50cm

Eileen Cooper Family Collection

I may have had the biological needs to make a human but I was not equipped for motherhood and I was pretty much in denial about the role for the first three years of my son’s life, where I lived with a constant anxiety that I was going to kill him by doing something wrong.

Every time I thought I have this covered I know what I am doing, the goal posts changed and we were straight into another phase of quickly learning new skills to be able to be present and a mother.

This is a role I am enjoying much more as my children become adults. I am a much better adult mother. The needs still change like the wind but I don’t have the constant deep down dread that I’m really messing this up.

The painting The New Baby from 1985 reminds me so much of the first day I was alone with my son, the fear and the love but also the dread of the future, his and mine.

Hannah Perry

Artist

Walking in Circles

2021

—

Oil on canvas

107 x 154cm

Collection Artist

On becoming a mother I came to the realisation that I had a deep rooted, unconscious, anti-feminist view of the role of a mother that is excruciatingly patriarchal. Like, the value of a mothers labour is somehow less than that of one's success in the professional, male dominated world. The lack of funding for childcare and the national pay disparities are not helping that notion either.

Childbirth may shatter you into pieces and while I allowed myself the time and grace to recover physically and mentally, I still feel divided into two parts.

To present a balanced fight between two dichotomies. Firstly, I am reading The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness by psychiatrist R D Laing, which contrasts the experience of the ‘secure’ person with that of a person who ‘cannot take the realness, aliveness, autonomy and identity of himself’, who consequently contrives strategies to avoid ‘losing his self’. Feelings and motivations derive from this condition of ‘being in the world’. Without this we suffer ‘ontological insecurity’, a condition often expressed in terms of ‘being dead’ by people who are clearly still physically alive. Laing argues that psychosis is not a medical condition, but an outcome of the ‘divided self’, or the tension between the two personas within us: one our authentic, private identity, and the other the false, ‘sane’ self that we present to the world.

A sort of comparison to the madness of personal alienation – being alienated from oneself. Something like the idea of the ‘Internal Crisis of Motherhood’ as referenced by Sylvia Plath’s poem, Morning Song. An assault on the senses – from the moment of labour and birth, an out of body experience that can leave you in recovery like the survivor of a car crash. A feeling like the world has just burst through the body, or, depending on the birth, been sliced out. Through love but also doubt, darkness and a crisis of confidence.

Perhaps to undergo an existential re-birth, via confronting the reality of existence itself.

A past self, a past body, a past life – now has to be mourned. A new self has been born or replaced with the leadened experience of that of generations of mothers who I cannot relate to. Stepping away from my own singular experience obstinately and acknowledging a shared experience of societal pressure and pain of women at large. I acknowledge an internalised misogyny. Something like the madonna-whore-complex – a psychological complex where men see women as either saintly Madonnas or debased whores. Men with this complex desire a sexual partner who has been degraded (whore) and cannot desire the respected partner (Madonna).

I went to a post-natal pilates class once with my youngest child when he was a few weeks old and still curled up like a prawn – fresh from being crushed in my body for 10 months. The teacher made a remark about how my child gazed into my eyes and how I gazed into his, how he ‘idolised’ me, how I was ‘his goddess’ and he was my ‘baby zeus’. This made me laugh, but also yes.

My space to create work, my identity, my friendships, self-care and my personal core beliefs are consistently at odds with my love for being a mother, for caring about my children's wellbeing and development, attending events and clubs with people who I have nothing in common with and struggling with being in the home in general.

I am confused about what world I exist in as a parent. It is all very unknown and as I have unknowingly created a divide between two polarities, I am still working on bringing them together - the previous self with my new role. But I am trying. Literally bursting open with heartbreak and with love.

A past self, a past body, a past life – now has to be mourned. A new self has been born or replaced with the leadened experience of that of generations of mothers who I cannot relate to. Stepping away from my own singular experience obstinately and acknowledging a shared experience of societal pressure and pain of women at large. I acknowledge an internalised misogyny. Something like the madonna-whore-complex – a psychological complex where men see women as either saintly Madonnas or debased whores. Men with this complex desire a sexual partner who has been degraded (whore) and cannot desire the respected partner (Madonna).

I miss the metaphorical lady of pleasure.

In turn, as a mother, I feel strangely content: I lack the ability to explain the overwhelming happiness I felt in becoming a mother… or my love for my children. The best I can express is the unfaltering happiness from the altruism of giving them care and watching them grow. Two beautiful funny excitable happy children who need me. A carer to dependents who need me to show up, be present and to comfort them relentlessly that in turn will offer an exchange of unadulterated love.

To the alarm clock of ear-splitting screaming, after multiple night wake ups, when you really have nothing left to give until the moment my child sees me, and I witness their sheer happiness and excitement just from seeing me walk in the room – just for existing. A love that bursts every part to the point that nothing else really matters. Lying naked staring into the eyes of a breastfeeding baby looking back at you without conditions. Still physically connected and keeping each other alive.

Caro Howell

Director, Imperial War Museum

Treasury

1985

—

Oil on canvas

244 x 183cm

Collection Artist

Motherhood, like art, is an exercise in experimentation, self-doubt, hope and struggle; equal parts joy and frustration, with an uncertain endpoint.

Rejina Pyo

Fashion Designer and Creative Director

Tickling Mummy's Toes

1985

—

Oil on canvas

121 x 91cm

Eileen Cooper Family Collection

Motherhood has been overlooked in art history, as there is scarcely anything bigger in real life than raising a human being. I, like many others, have experienced the guilt that comes with wanting to be with your children and a desire for a career. Blinded by love for them, but also exhausted, oscillating between feeling trapped and blessed by them.

I love how Eileen depicts motherhood. It's playful, but deeply complex and ambiguous, which begs of you your own experience, engaging with the viewer.

Denise Riley

Poet

Which What Why

1991

—

Oil on canvas

122 x 122cm

Collection Artist

One day after school, her small son asked ‘Will you be dead with me, at the end of the world? Does it hurt when you get dead? Our teacher told us about that today. You have to hold your fingers together flat and straight up, like this – look! you aren’t looking! – then you say Amen, we all had to do that. I want something to eat, we only got carrots for lunch today’.

Trying to finish her writing day’s work, she replied that No, being dead didn’t hurt at all, he wasn’t to worry, and to check the fridge to see what was in it and let her know. How very much she didn’t want him troubled. Though to his question about being with her at the end of the world, she could say Yes.

Helena Lee

Author and Features Director of Harper’s Bazaar, Editor of Bazaar Art

Sentimental Mood

2019

—

Oil on canvas

76 x 61cm

Private Collection

This is a story of friendship and growth. How empathy can gently take you in different directions. Because, what a new mother needs, above all else, is empathy – an understanding that the overwhelming responsibility of parenthood comprises daily heartache and joy, that every endeavour to shape and nourish a life plumbs the depths and reaches the extremities of human emotion.

I didn’t think, after the birth of my second child Margot, that I would make new friends. But then I met the artist Eileen Cooper in a chance encounter at a traffic light near our houses. We first came across each other on the cusp of spring when Margot was weeks-old, when her breath was cloud-like, and eyes still blue. On the discovery that we were almost neighbours, Eileen invited me over for a cup of tea with her customary warmth. Our friendship can be measured with Margot’s milestones: smiles, laughs, her body unfurling like a flower from a tight new-born ball as weeks, then months passed. Eileen inhabited a mother’s sensitivity, ensuring I had coffee, tea, ginger biscuits at hand, offering me lifts home during sudden rain showers, taking Margot while I rearranged myself after a feed – patient with the whimpers and mews of this small creature. She would look into Margot’s eyes and discern how light they were, striking given her half-Chinese ethnicity, and then note with an artist’s assurance (and a smile) how creative she was going to be.

It was during these meetings that we’d enjoy long conversations, about the way her imagery mythologised the modern woman, the experience of liberation and loss as children grow up, or just about what we’d done that day. After a few weeks, Eileen said she had an idea for a mother-baby drawing, would I be interested in taking part?

Remembering the transience of this period of motherhood I was immersed in, I said yes. And so, one April morning Margot and I find ourselves in Eileen’s drawing studio, her son Sam’s old bedroom on the second floor. I’m invited to sit in a low, blue chair with sloping arms. The light is bright, but not overly so, tempered by the ashen clouds overhead. I settle Margot, who is fascinated by Eileen’s sculptural face and calm demeanour, to face outwards, perched on my knee. Eileen is swift. She outlines my hair and face with charcoal on paper: the round of Margot’s head, strokes of blue for her eyes, the impression and knot of my fingers.

After a while, after Margot has discovered her toes, she starts to dribble. I ask if I can feed her, aware that I have to change position. Eileen graciously stops working on the drawing. Margot relaxes into contentment while I put her to my breast. I suggest that Eileen capture what’s before her. ‘Are you sure?’ she says with genuine concern, then pauses: ‘What a privilege’. She starts a new piece, maps out my lopsidedness and angularity, runs the dark blue used in my dress into my hair, then interlocks the baby’s shape into mine – the length of her body, from her full cheeks to her chubby toes, conscious of the intimacy, perhaps even the responsibility of the moment.

I am at ease at being looked at, because there is a fluidity and gentleness to Eileen’s process, knowing that the femininity of the idea that informs the painting will ultimately be more important than the specifics of whether my hair is tucked behind my ear, or whether Margot keeps perfectly still. Eileen imposes no restrictions or rules, feeling through the situation as naturally as it happens.

This painting is not a portrait. It is as much about Eileen as it is about me. She once told me that she struggles to make her images universal, but I do not see the struggle, only the reward of the power of her art. I see a nobility to this quiet ambition to capture the essential nature of womanhood, to convey the universality and timelessness of the experience. The woman in the painting is every mother. The woman in the painting is me.

An edited version of an essay entitled ‘Turning Points’, first published in Eileen Cooper: Personal Space exhibition catalogue, Huxley Parlour Gallery, London, 2019.

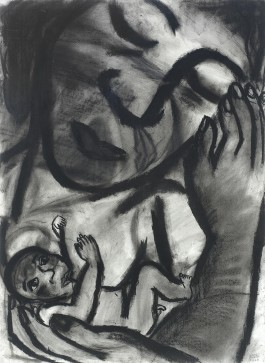

Eileen Cooper RA

Late Night Feed

1985

—

Charcoal on paper

76 x 56cm

Eileen Cooper Family Collection

When my two sons were very small and parenting was a struggle someone gave me great advice. She said, ‘You only need to be a good enough mother.’ This has stayed with me, it helped me keep things in perspective and to stop being hard on myself, as I think all mothers are.

It now seems so long ago, 40 years since I had my first child, now I have grandchildren. Reading the quotes from some of the younger mothers who have generously written about my work, I’m reminded how raw and intense it is, joyful yes – without a doubt, but anxiety, exhaustion and loss of self are all here.

I’m incredibly grateful to Kathleen Soriano for curating this online exhibition and to the women who've found the time in busy lives to write for me.

Voyage

2009

—

Screenprint

31 x 39cm

Edition of 12

Back to top

© 2024 Eileen Cooper